4 big trends for China and Russia in 2019

Hi Everyone,

A special edition of The Report covering four big trends for China and Russia in 2019: The Economy/Energy Markets; Apprentice Season 3: The Moscow Project (and sanctions); The Ghosts of Authoritarian Political Interference Past, Present, and Yet-to-Come; and Central and South Asia.

1) The Economy/Trade

Events within and between China and Russia in 2019 will largely be determined by the world economy. The chances of a world recession are rising: Goldman Sachs pegs the probability of a recession occurring in the next year at 50%, although some economists are more optimistic.

The Chinese and Russian economies could weather a small, short recession: Russian governmental debt stood at only 15% of GDP in 2018, while Chinese governmental debt (including local government debt) appears manageable at about 60% of GDP. Both sides will likely try to “buy” their way out of any recession by expanding debt. Indeed, China is de-de-leveraging: new December 2018 loans were about 20% above analysts’ forecast. It’s entirely possible that both economies will overcome short-term difficulties through fiscal/monetary stimulus.

But there are major risks and vulnerabilities. Russian real incomes appear to have fallen every year since 2014 (a note of caution: interpreting Russian economic data is often tricky due to Rosstat’s creativity and exchange-rate fluctuations). In China, meanwhile, some observers (such as Michael Pettis) maintain that actual GDP growth is much lower than reported. While credit markets do not function efficiently in either country, the Chinese government may have systemically misallocated credit for over a decade, with potentially disastrous consequences for national, regional, and world economic development. Pettis writes: “When you speak to Chinese businesses, economists, or analysts, it is hard to find any economic sector enjoying decent growth… In my eighteen years in China, I have never seen this level of financial worry and unhappiness.”

A sharp downturn or a prolonged recession could lead to domestic political difficulties for both regimes. Putin’s approval ratings are at a post-Crimea low amid unpopular pension reforms, weak growth, and rising inequality. The CCP is unsure of how the Chinese people will adjust to the first period of declining living standards in over 4 decades. Some Western observers have speculated that Putin and/or the CCP will respond to declining economic growth by seeking to “externalize weaknesses.”

In a 2016 article for Foreign Affairs on “The Risks of Chinese and Russian Weakness,” Robert Kaplan noted: “Whereas aggression driven by domestic strength often follows a methodical, well-developed strategy—one that can be interpreted by other states, which can then react appropriately—that fueled by domestic crisis can result in daring, reactive, and impulsive behavior, which is much harder to forecast and counter.”

Kaplan’s proposition is debatable: some scholars find little empirical support for diversionary war theory. On the other hand, Vladimir Putin’s decision to annex Crimea in 2014 was largely motivated by domestic political concerns. The coming year might see a battle between the TV and the refrigerator in Russia and/or China.

China-Russia Trade

The two sides expanded their trade relationship in 2018. According to a press release from MOFCOM, China and Russia conducted over $100 billion in trade in 2018, largely due to rising energy prices and a doubling of capacity along the ESPO pipeline. While detailed trade statistics from 2018 are not yet released, data from the previous 5 years demonstrates some features of the trading relationship. First, China has enjoyed a slight surplus* for several years.

*usual caveats about Chinese/Russian economic data apply

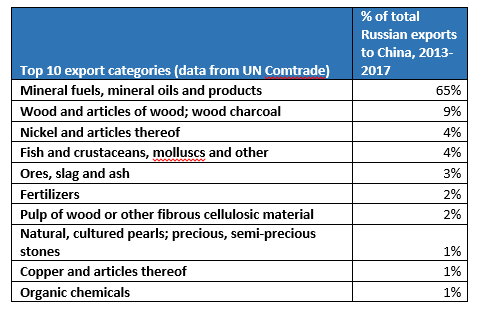

Second, Russian exports to China are overwhelmingly concentrated in commodities. In most years, oil constitutes about 60% of Russian exports to China.

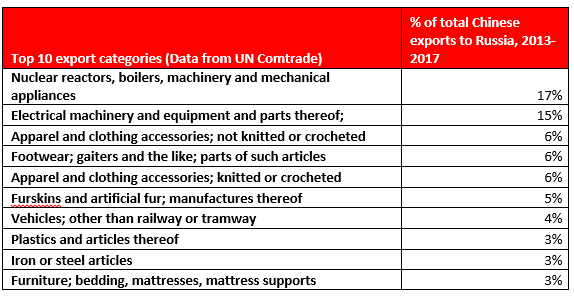

Chinese exports to Russia, on the other hand, are much more diversified:

Energy Markets

In 2019, commodities will remain the most important feature of the trading relationship, albeit with a subtle wrinkle: gas is becoming an increasingly important element in the China-Russia economic relationship. First shipments from the Power of Siberia gas pipeline are scheduled to arrive in China in late December 2019. A defining question for the year is whether or not the two sides will ink a deal for the Power of Siberia 2/Altai gas pipeline to Western China.

Other trends in commodity markets are worth watching: relentless technological and financial innovations have lowered breakeven prices (the price at which a project is profitable) for oil producers, increasing global supply and limiting rents for oil-dependent economies, such as Russia. Will US tight oil and shale gas production continue to become more efficient? Lower energy prices benefit the Chinese economy but limit the Russian economy.

China is not a passive actor in energy markets. Besides pursuing considerable investment in clean energy, Chinese gas companies quietly expanded shale gas production by 40% in 2018, albeit from a low starting point. Watch for Chinese clean energy investments in 2019, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa.

China and Russia often cooperate on energy, but consumer-producer interests are often contradictory. How the two sides manage their respective energy interests in 2019 will reflect and inform the broader relationship.

Putin will also likely decide this year whether or not to proceed with the $25 billion USD Moscow-Kazan high-speed railway [Russian language link]. The project would be a significant boon for Chinese rail companies. Chinese-made rail cars, however, are facing scrutiny in Washington amid cybersecurity concerns. Russian officials trust their Chinese counterparts (and the two sides would never spy on each other, of course) but Putin might decide the economics of the project are unfavorable.

Relatedly, will Russia use Chinese infrastructure for 5G networks in 2019? In September, the Global Times announced Huawei would construct a 5G network in Russia. In December, however, TASS announced that state-run companies must shift to locally-produced software by 2021. While notionally directed against the West, software indigenization also excludes software from another country that borders Russia.

China’s growing technological and economic hegemony – and Russia’s acquiescence or growing discomfort – will be a major economic and political theme in 2019.

2) The Apprentice Season 3: The Moscow Project (and sanctions)

Special Counsel Robert Mueller and other actors in the US Justice Department will likely indict more members of Donald Trump’s inner circle in 2019, possibly even Donald Trump himself. The Mueller Investigation’s findings could substantially increase demands for additional sanctions on Vladimir Putin’s Russia; lead to more calls for a pan-democracy election integrity alliance; ratchet up Western-Putin tensions, or lead to full-blown democracy-autocracy tensions. Alternatively, maybe Trump’s 30 years of contacts with the Soviet Union and Russia are nothing more than a series of harmless, disconnected events. Whatever the case, Trump’s domestic political standing and foreign policy actions will be highly unpredictable in 2019.

Observe The McConnell Line closely (I think Nate Silver may have first invented this concept). Similar to the Mendoza Line in baseball, The McConnell Line reflects a Trump approval rating at which Trump-supporting Senators are at greater risk in a general election than in a primary. For instance, if Trump’s approval rating stands at 30% on Election Day 2020 – and Trump is a nominee for President – many (most?) Trump-supporting Senators are highly likely to lose in the general election. If, however, Trump maintains an approval rating in the 40-45% range by Election Day 2020 (and Trump is a nominee for President), most incumbent Senators are favorites to win re-election in a general election; their primary political concern will be a primary challenger. US Senators and US Vice President Mike Pence will become increasingly important actors in US domestic and foreign policy in 2019.

US domestic politics will, of course, have implications for China and Russia. Trump may respond to growing unpopularity by seeking a “small, victorious political/economic/military campaign” against Iran, North Korea, or Venezuela. Although Trump will likely continue to apply more political/economic/Twitter pressure on Iran, the probability of an actual, sustained military conflict is low to moderate: war with Iran would disturb oil markets, severely damage the US recovery (and the Chinese economy, although Putin might not be displeased with higher oil prices), and politically imperil Trump. That said, the White House apparently asked for military options in Iran last fall. John Bolton in particular is thought to be very hawkish on Iran.

Trump’s policy towards North Korea is a more uncertain and consequential, but Kim (along with many other foreign leaders) appears to have become quite adept at flattering Trump in exchange for substantive concessions. Trump isn’t interested in Venezuela, although it does excite some of his advisers. If Trump becomes more erratic because of domestic pressures he may inadvertently set off a crisis. It’s unclear if his advisers would challenge him or restrain his actions. May you live in interesting times.

Anti-Putin sanctions appear increasingly probable in the US domestic political context. A few notes on sanctions. First, the US and other Western countries are often careless in how they frame sanctions. Peter Harrell wrote a piece in Foreign Affairs noting “How to Hit Russia Where It Hurts”. Framing sanctions as anti-Russian (rather than anti-Putin), plays directly into Kremlin propaganda.

Second, is there a way to strategically structure sanctions? The broadly defined West will need Russian support to balance the Indo-Pacific in the coming decades. Arguably, sanctions should be easily terminated after Putin leaves office, whenever that is: the Jackson-Vannik amendment to the US Trade Act of 1974 inhibited US-Russia economic relations, particularly in the 1990s. Sanctions should arguably punish Putin while leaving the door open for cooperation with a more responsible Russian government.

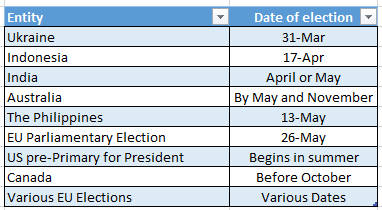

Sanctions (or the absence of sanctions) against the Russian government, the Chinese government, or both over political interference will be a defining element in 2019. The Special Counsel’s findings could amplify Congressional legislation for measures to protect democracies from future authoritarian influence and punish Putin’s previous perfidiousness.

3) The Ghosts of Authoritarian Political Interference Past, Present, and Yet-to-Come

A lot of ink has been spilled over authoritarian political interference, but the democracies have managed this threat very, very poorly and have yet to institutionalize counter-interference mechanisms. Time will tell if the democracies develop a NATO-like organization for political interference.

Technological “advances” have made it easier to create videos that appear realistic but swap one person’s face for another, and individuals of all sorts have troubles distinguish fiction from fact (if you’d like to ruin your Wednesday, read this NPR report about a Stanford study on readers’ discernment ability). About 30 percent of Americans say they believe former US President Barack Obama was born in Kenya; 8 percent of surburbanites in highly-educated Marin County [according to Tom Nichols’s excellent book] requested an exemption from vaccinating their children in 2012. And the US is, relatively speaking, a highly educated country. The US enjoys near-universal literacy, compulsory secondary education, and widespread post-secondary attainment. Many other countries aren’t so fortunate and may be even more vulnerable to disinformation campaigns than the US. Authoritarian governments will continue to weaponize ignorance and exploit confirmation bias in 2019. May you live in interesting times.

If you’re interested in further reading on this topic, Power 3.0 has an excellent blog called Understanding Modern Authoritarian Influence.

4) Central and South Asia

South Asia (India, Afghanistan, and Pakistan) may have eclipsed Central Asia’s importance to both Russia and China. India is emerging as the world’s third superpower, presenting uncertainties for China and opportunities for Russia, which is seeking to diversify its economic, political, and military partners. The three sides resumed the RIC (Russia-India-China) trilateral in 2018 after a 12-year hiatus. Russia has also strengthened its security ties with the South Asian country, including through the sale of the S-400 missile system.

Russian officials have framed growing Russia-India security cooperation as a way to undermine the US presence in Asia, which is a true lie: Putin would indeed love to displace the US from the Indo-Pacific, but he also likes maintaining options and reducing dependence on China when possible. China regards India warily and prefers not to dilute its influence in multilateral arrangements. It’s unclear if the RIC forum will continue or not in 2019.

Tensions between the PRC and Central/South Asian societies are growing due to the repression of Muslims in Xinjiang and Chinese infrastructure lending, which may be driving Pakistan and other BRI countries into a “debt trap.” Central/South Asian elites, meanwhile, generally welcome Chinese economic ties and acknowledge the region’s geographical and political realities, but are concerned by Chinese debt. It’s not clear if Russia will leverage the situation to re-assert its dwindling economic, political, and security influence in Central Asia. Also noteworthy: Russia’s growing security engagement in Afghanistan will affect neighboring countries, including nuclear-armed Pakistan.

Turkmenistan may experience dramatic economic and political changes in 2019. The country’s ongoing economic depression could result in the ouster of Turkmen strongman Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow. Turkmenistan competes with Russia to supply gas to China.

Uzbekistan’s economic reform program could continue to integrate the region and provide a counterweight to both of the major authoritarian powers. There are credible rumors in Kazakhstan, meanwhile, that fresh elections will be called and that Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev will not step down from office. Turkmenistan’s planned Central Asia – China Pipeline (CACP) Line D gas expansion project would likely transit Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan territory before reaching China. It could be an eventful year in Central Asia.

5) Sui generis/third party events

A bonus feature: because four trends aren’t enough! What else will be significant this year? Belarus? Ukraine? A PLA(N) ship ramming an Indonesian coast guard vessel? A computer or physical virus proves highly infectious and leads to economic paralysis? A leader in Central Asian passes away unexpectedly? Mysterious hacking of Western news media ahead of the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre? Something else? Events & trends that seem blindingly obvious in retrospect are often unpredictable in the moment.

One thing can be predicted with absolute certainty: there will be a lot to discuss this year. Thanks for reading.

v/r,

Joe Webster

The China-Russia Report is an independent, nonpartisan weekly newsletter covering political, economic, and security affairs within and between China and Russia. All articles, comments, op-eds, etc represent only the personal opinion of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the position(s) of The China-Russia Report.