Beijing backed Moscow in oil markets in 2022, at seemingly great cost

In 2022, Beijing bought crude oil at the top of the market then declined to refine it into valuable products.

Editor’s Note: Correction to article.

I received some feedback on this article from a professional acquaintance who works at Kpler, a commodities market data firm. The colleague says that a Reuters story from December 2022, cited by this article, doesn’t accurately reflect Chinese crude oil storage volumes. Instead of Chinese crude oil inventories rising by over 230 million barrels, as Reuters claims, Kpler states that volumes in storage were flat. While both Kpler and Reuters are highly credible sources of information, I find that Kpler’s methodology is more robust, in this instance. You can see more explanation here.

China is considering providing "lethal support" to aid the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine, according to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken. While there is already considerable evidence that Beijing is backing Moscow in its confrontation with the West, its support may be moving to a new phase.

In a somewhat below-the-radar but potentially even more consequential development for the Western-Russia confrontation, the IAEA reports Iran has enriched uranium to 84% purity, a level just below that needed to produce a nuclear weapon. Tensions with Iran over any nuclear weapons program could easily send energy prices even higher; harm consumers, thereby undermining Western political support for Ukraine; and support Russian export earnings. There is a risk that Moscow might attempt to exploit Western-Iran tensions; it might even be stimulating them.

A full, standard version of The Report will be published later in the week. Below find a discussion of how Beijing’s actions in oil markets supported Moscow.

Beijing backed Moscow in oil markets in 2022, at seemingly great cost

In 2022, Beijing bought crude oil at the top of the market then declined to refine it into valuable products.

The PRC’s actions in energy markets in the post-war period suggest its actions have largely been motivated by politics, not economics. Beijing filled its crude oil inventories at the height of the market but declined to export refined products despite extraordinarily supportive refining margins. This strategy was almost certainly highly unprofitable for China but filled the Kremlin’s coffers and amplified transport fuel inflation, providing crucial economic and political assistance for Putin. Beijing supported Moscow in energy markets in 2022, likely at great cost to its own economy.

China filled its inventories at the height of the market

Beijing evidently used Russian crude oil to replenish its crude oil inventories in 2022. In May, Bloomberg reported the two sides were in talks about using Russian oil supplies to fill China’s strategic reserves. While the two sides appear to have never formally inked an agreement, at least publicly, China almost certainly used Russian exports to build its oil inventories, as Reuters reports 0.7 MMBPD of crude oil entered Chinese inventories for the first 11 months of 2022. While China’s customs data shows Russian crude imports in this period rose 10% from prior-year levels, or by about 0.16 MMBPD, additional barrels from Russia (as well as other sanctioned entities, such as Venezuela and Iran), were almost certainly recategorized as “Malaysian.”

Beijing curiously filled its inventories with Russian crude oil at the peak of the market even as Brent spot prices reached their highest nominal price level since summer 2008. Most countries were, conversely, drawing down their storage levels over this period, adding supplies to a very tight market.

While China very likely secured some discount on the prices of crude oil imports, Beijing still declined to process these volumes into gasoline, diesel, or jet fuel, despite extremely favorable economics. This “buy high, move into storage” strategy does not have any apparent economic rationale but makes more sense if Beijing sought to provide plausibly deniable but critical economic and political assistance to Putin.

The curious case of the missing refined products exports

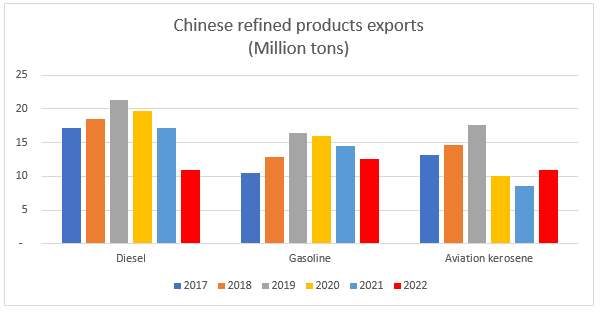

Beijing is, typically, one of the world’s most important exporters of refined products such as gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and more. In January 2022, however, China’s initial export allotment reduced export quotas for refined fuels (predominantly gasoline, diesel and aviation fuel) to 13 million tons, down 56% from 29.5 million tons in 2021’s first allotment. Although Beijing issued a new fuel export quota in September, bringing its total quota allocation to 37 million tons, China’s 2022 physical exports of diesel and gasoline fell y-o-y by 14 percent and 37 percent, respectively. These supply shortfalls played a significant role in driving up world diesel and gasoline prices.

Source: China’s General Administration of Customs

China’s refusal to expand refining production throughout most of 2022 was immensely curious. Due to growing post-COVID energy demand, the shuttering of about 3.3 million barrels per day (MMBPD) of world refining capacity, lower crude products world inventory levels, and uncertainty surrounding Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, refining margins exploded over summer 2022, increasing profitability for refined products such as gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel. China declined to expand export quotas over the summer, however, leading Ben McWilliams of the Bruegel think tank to describe the bottleneck as “policy rather than pipes.”

Source: China’s General Administration of Customs (2020 omitted due to COVID)

There are several potential non-geopolitical rationale for Beijing’s desire to restrict exports. From a technical perspective, refinery ramp ups can take some time. Perhaps more importantly, the domestic political economy of China’s refining sector is extremely complicated. In 2012, Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping purged Zhou Yongkang, a former Politburo Standing Committee member, security czar – and former head of state-run China National Petroleum Company (or CNPC, also the parent company of PetroChina). CNPC is a major player in Chinese refining markets, may have residual ties to anti-Xi factions, and suffers from low refinery utilization rates. Xi may therefore have been reluctant to undertake an action that could have benefitted potential domestic rivals. Additionally, the January 2022 protests in Kazakhstan were largely sparked by rising transportation fuel costs and may have spooked Beijing into implicitly subsidizing domestic market consumers by closing export channels.

Still, Beijing’s refusal to increase refinery throughput for most of 2022 was enormously curious. Not only would Chinese refineries have directly benefitted from higher utilization rates but, far more importantly, additional diesel and gasoline availability would have, all things being equal, immensely benefitted the world economy through lower inflation, lower interest rates, and higher GDP growth, providing significant fundamental support for Chinese exports.

Whatever Beijing’s calculus, the run-up in fuel prices this summer was enormously useful to Putin, who seeks to leverage economic damage from the invasion of Ukraine to tip the scales for Kremlin-friendly populists in Western elections and win the war indirectly, via political rather than military means.

Buy high, then store

In sum, Beijing’s oil strategy in 2022 was to fill its inventories with imported Russian crude at the height of the market, then decline to export refined products such as diesel, gasoline, and jet fuel. This policy had the effect of amplifying global inflation, inflicting pain on world consumers, driving up poverty rates around the world, and supporting the Kremlin’s objectives - at substantial costs to Beijing’s own economic interests. In the confrontation between the West and Moscow, Beijing’s oil strategy in 2022 is yet another piece of evidence indicating which side Beijing supports.

Joe Webster is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and editor of the China-Russia Report. This article represents his own personal opinion.