Imports from China are critical for the Russian war economy

How the West can apply selective pressure to Chinese exporters

This edition features an analysis co-authored by Janis Kluge, an expert on the Russian economy at SWP, and me. Thanks for reading. - Joe

Imports from China are critical for the Russian war economy

How the West can apply selective pressure to Chinese exporters

By Janis Kluge and Joseph Webster

China’s economic ties to Russia are uniquely important for the Kremlin’s war effort. While attention has typically focused on Russia’s exports of crude oil and products, sanctions on Russian energy are not enough to make a difference on the battlefield in the short term. As long as Russia enjoys the inflow of hundreds of billions of petrodollars, imports are the Achilles’ heel of its war effort. China’s direct and indirect exports to Russia are playing an outsized role by limiting goods shortages, restraining inflation, and providing logistical support for the Russian military.

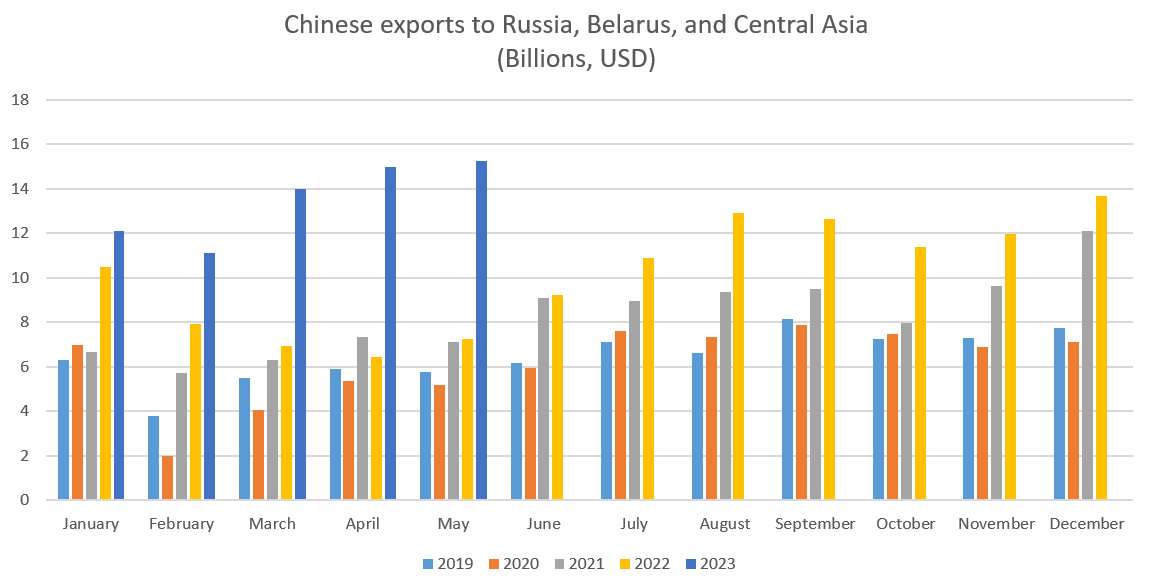

While nearly every other country has slashed exports to Russia, direct Chinese exports to Russia and indirect trade via “cutouts,” like Belarus and several former Soviet Union countries, are climbing rapidly. China’s year-to-date goods exports to Russia are 81 percent above same-period levels in 2021, while China’s goods exports to Belarus and Central Asia over the same period are up 140 percent, according to our analysis of official Chinese trade data.

Western policymakers must strike a difficult balance: economic ties with China are a sensitive issue as increasing tensions with the world’s second-largest economy could have repercussions for domestic businesses and even weaken the political support for governments in Germany and other NATO countries. At the same time, the West must also limit Beijing’s war-enabling exports to Moscow by applying selective pressure to critical exports. Navigating these contradictions will prove challenging, but first the West must admit that Chinese goods exports to Russia are a severe problem.

Reducing Russian exports is a long-term strategy

Although Western sanctions on Russian exports have already dented the inflow of foreign currency to Russia, its export revenues still comfortably cover its import needs and even extend loans to deepen cooperation with countries such as Turkey and Iran.

Because the West cannot easily push Russian oil supply out of global energy markets, Russia will have enough dollars and yuan to pay for imports for the foreseeable future, as long as it finds willing trade partners abroad. For Russia, money is not the issue, particularly when it comes to the import of goods that are critical to its war against Ukraine. This is why the West must try to stop these imports directly by making it as hard as possible for Russia to find willing business partners. As recent data shows, the key to this lies in trade with China.

Chinese direct and indirect exports to Russia are uniquely problematic

While China has often refrained from investing into Russian companies and generally maintained technical compliance with sanctions, its exports to Russia are most important in the near-term. While trade data involving Russia has become increasingly politicized and partially censored, our country-by-country analysis for 82 countries reporting results for 2021-22 shows goods exports to Russia fell by 17 percent in 2022 to $213 billion. The vast majority of medium and large economies saw exports to Russia fall, with China, Belarus, Turkey, and several CIS countries comprising the major exceptions. China’s direct goods exports to Russia rose $8.6 billion to reach $76 billion in 2022, according to official Chinese trade data, constituting about one-in-three of Russia’s total goods imports, as measured by value. Between growing bilateral trade volumes in the new year, indirect shipments via “cutouts” such as Belarus and Central Asia, and smuggling and underreporting, China’s share could be even larger.

Sources: PRC General Administration of Customs, Authors’ Calculations

Chinese goods exports provide critical strategic support. China exported nearly 23,000 heavy-duty trucks to Russia in the first five months of this year, more than eleven times the level in the same period in 2021. Chinese truck makers, which had not played a significant role in Russia before the war, now make up more than 50% of new trucks sold in Russia. China’s exports to Russia (and Central Asia) of spare parts are also up sharply, enabling the Kremlin to repair its civilian and military vehicle fleets.

Sources: PRC General Administration of Customs, Authors’ Calculations

While part of the surge in China’s truck exports is explained by the rise of its domestic auto industry, these vehicles may be enabling the Russian heavy duty truck manufacturer, KAMAZ, to shift production lines to armored vehicles for Russia’s military. Indeed, KAMAZ’s production includes vehicles that were seen in Belarus carrying missiles for Iskander missile systems, according to a US Treasury sanction notice.

In addition to physical deliveries of trucks, Chinese technology has been useful for the Russian war effort, as Chinese exports of integrated circuits to Russia in 2022 tripled from 2021 levels.

Studies on the strategies of Russian businesses under sanctions confirm the paramount importance of Chinese support. In a survey done by the Moscow-based Gaidar Institute, 67% of Russian companies state that they have solved the problem of sanctions on Western machinery by switching to Chinese suppliers.

It is difficult to say how much of this is the Chinese government’s doing and how much is just businesses taking advantage of opportunities. But there is also no indication that the Chinese government is taking action to slow down sanctions circumvention. It is also clear that Beijing does not want to see Putin fail in Ukraine, it does not want a Ukrainian victory, and when push comes to shove, it may consider supporting Russia more openly.

Is it possible to change Beijing’s calculus?

While Chinese exports to Russia are highly problematic for the West, stopping these flows will prove difficult. Still, although Beijing has demonstrated it will maintain its pro-Russian “neutrality”, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has created serious dilemmas for China.

The war has already degraded China’s economic growth. China is the world’s largest exporter of manufactured goods, as well as the largest importer of oil, natural gas, coal, and agricultural products. We conservatively estimate that the economic disruptions, commodity price spikes, and resulting interest rate increases caused by the war lowered Chinese GDP from baseline estimates by at least $140 billion USD, or roughly 0.7 percent of Chinese output.

The war’s long-term consequences could be even more serious for the Chinese economy if Beijing keeps exporting sanctioned goods to Russia at the current pace. Beijing’s support for Moscow has deepened skepticism of the PRC in Western capitals, especially regarding technology. In addition to the United States, the Netherlands, Japan, South Korea, and other Western countries are all restricting their technological ties with China, especially in critical semiconductors.

Despite these immense direct and indirect costs of the war, Beijing has done little-to-nothing to oppose Russia’s aggression. China’s economic interests have so far been trumped by its geopolitical interest of keeping Putin in power and Russia as a partner in countering the US. Still, although Beijing is willing to pay a price a steep cost for Putin, its commitment is not unlimited, particularly if it sees that Russia’s war is likely to become a failure. Beijing seeks to maintain economic ties with the West, especially Europe. China’s support for Russia will depend on the price tag that the West attaches to it.

Selective pressure

While the West likely cannot change Beijing’s pro-Russia orientation, and should be very wary of applying broad secondary sanctions against the world’s second-largest economy, it may be able to selectively pressure PRC exports of strategic goods and services to Russia. For this to work, the West would have to focus on a small set of high-priority goods such as drones, semiconductors and critical dual-use or military goods, clearly explaining to Beijing how these particular items are facilitating Russia’s war on Ukraine.

In addition to continuing to communicate to Beijing that supplying lethal aid to Moscow would severely damage relations with the West, Washington and Brussels should examine the costs and benefits of sanctioning specific Chinese companies and exports to Russia that enable the war effort. Potential candidates for sanction include producers of dual-use goods such as heavy trucks, spare parts suppliers, and more. Finally, Western countries must ensure that their own companies are not knowingly or unknowing violating sanctions by exporting these products to Russia.

Selectively pressuring Chinese exports to Russia will prove difficult and comes with risks. But as Chinese exports to Russia are posing a unique security problem for Ukraine and other Western countries, Washington and Brussels must act.

Janis Kluge is a Senior Associate at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs. Joseph Webster is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. This article reflects their own personal opinions.