I’ll publish another update today on the PRC’s response to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, but first I want to discuss a topic that’s an underappreciated element in the crisis: Central Asia. Included in this edition are two articles:

1) Putin’s war and Central Asia;

2) More Central Asian natural gas headed to China?

1) Putin’s war and Central Asia

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is draining Russia’s “hard” and “soft” power in Central Asia and shifting the region’s power balances. The invasion will likely limit Russia’s ability to project hard power, produce economic pain for Central Asian migrants, and sharply accelerate the PRC’s rise in Central Asia.

The Russian military’s performance in Ukraine is not yet determined but will have important implications for Central Asian security. While it is still very early days in the military campaign, the Russian military appears to have suffered thousands of casualties, lost hundreds of vehicles, and, bizarrely, even failed to suppress Ukraine’s air capabilities. Casualties and costs may also rise dramatically if Russian forces enter major cities. Russia’s intervention in Ukraine is degrading its ability to oversee Central Asian security, while its subpar combat performance, if sustained, may alter the calculus of Central Asian elites.

Russia traditionally has assumed leadership in Central Asia due to its overwhelming conventional military might and overlapping political interests with regional governments. Still, there are potentially important exceptions revolving around economic interests (particularly energy exports). Additionally, with Russian conventional forces perhaps not as effective as previously believed, Central Asian governments may also have greater confidence in their ability to withstand military pressure and may be increasingly willing to pursue independent foreign policies. Russia’s security leadership role in Central Asia is diminishing by the day and may not survive the war in Ukraine.

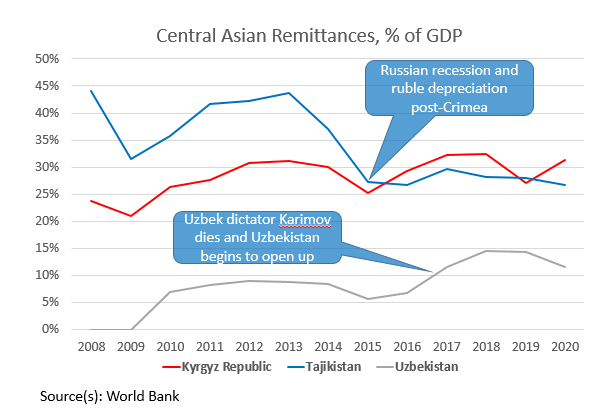

The economic consequences of the war will be felt almost immediately via remittances, as well as fuel and commodity prices. With Russia facing some of the world’s strongest sanctions to date, Central Asian laborers in Moscow, St. Pete, and other Russian cities will almost certainly send less money home. Nationals from those Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan appear to comprise the majority of Central Asian laborers in Russia, although data from Turkmenistan is as unreliable as ever. Kazakhstan, the region’s wealthiest and best-governed country, may actually be a net importer of laborers.

Fuel and commodity prices are likely to rise but will have an unclear impact on the region. Central Asian economies are often not very well integrated into global markets and also have idiosyncratic trade characteristics (i.e. exported commodities vary by country and include not only oil and gas but also cotton, gold, etc). Putin’s invasion will likely carry implications for the region’s hydrocarbon markets, however. With Kazakhstan recently experiencing economic protests over rising transportation fuel prices, regional governments are doubtlessly attentive to consumer pain at the pump. Indeed, Kazakhstan could actually benefit from the war in Ukraine due to higher crude oil prices. Previous emergencies, such as the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, the 2014 Remittance Crisis and COVID, seem to have had little impact on per-capita income growth – at least as reported in official statistics. (Parenthetically, the region’s economic data is of highly dubious quality, particularly in Turkmenistan. It may be useful for observers to monitor on-the-ground reporting, and food prices.)

Finally, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine will sharply accelerate the region’s power transition. Russia seems likely to face a severe economic recession from sanctions and a potentially disastrous military defeat in Ukraine; Central Asian elites and publics also appear discomfited by Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and general lack of respect for post-Soviet borders. These factors cannot but reduce Russian hard and soft power regional capabilities, offering a vacuum that Beijing will fill by dint of its massive economic regional presence. Beijing identifies Central Asia as only a tertiary priority and will tread very carefully in an area Moscow regards as its backyard. Beijing will likely continue to flatter Moscow’s regional pretensions, but there are signs that the PRC may be seeking a larger presence in the region due to its natural gas interests.

2) More Central Asian natural gas headed to China?

Central Asia may be in the initial phases of a natural gas renaissance. Serdar Berdymukhamedov’s elevation to the Turkmen presidency is fraught with uncertainty but could augur economic reforms in gas-rich Turkmenistan. Uzbekistan is undertaking economic transformation, prospecting for shale gas, and opening itself to foreign trade and investment. The outcome of these events and trends is hardly foreordained: Uzbekistan’s gas reserves are still unknown but may be insufficient, and one should never underestimate the incompetence of the Turkmen elite. Still, there are hints that Beijing may be eyeing additional natural gas and energy imports from the region. The stars may be aligning for Central Asian natural gas.

Turkmenistan succession, natural gas, and China

Turkmenistan, home to the massive Galkynysh gas field, is the most important natural gas player in the region. One of the biggest obstacles to Turkmen natural gas exports may be on his way out, as Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov announced on February 11th that he will step down and anointed his son, Serdar, to become the next President. The succession announcement’s timing is noteworthy: it took place less than a week after Gurbanguly met in-person with the Chinese leadership in Beijing on February 5th.

Did Beijing urge Gurbanguly to step aside? Potentially. China has the means and motive to intervene in Turkmen politics: China’s CNPC is heavily invested in the Galkynysh gas field, falling Turkmen production contributed to a Chinese gas crunch in the 2017/2018 winter, Gurbanguly has taken unexplained long absences due to health problems and/or coup threats, and China’s natural gas needs are growing. Finally, China may regard Turkmenistan as a lever in its natural gas negotiations with Russia over the Power of Siberia-2 natural gas pipeline. Beijing may have played a role in Gurby’s retirement given the timing and context of the announcement.

Would a political transition in Turkmenistan make the country a more reliable natural gas exporter? It’s far too soon to say. Serdar’s personal qualities will likely prove decisive, but the 40-year-old is something of an enigma, and any reform program would encounter significant domestic opposition. Still, Serdar does have significant experience dealing with natural gas and the intersection of great power rivalry: he worked at Turkmenistan’s Moscow embassy during Russia’s notorious “vacuum-bombing” of a Turkmen natural gas pipeline in May 2009. Serdar’s ability to overhaul Turkmenistan’s natural gas export capacity is unknown, but he does have significant geopolitical experience and, importantly, may have some supporters in Beijing.

Will Uzbekistan reforms and geology align?

Tashkent has displayed an uneven level of energy sector ambition but could be on the cusp of a natural gas revolution. Uzbekistan is facing its own domestic energy shortages and watched transportation fuel-driven economic protests in Kazakhstan with great concern and currently plans to halt natural gas exports by 2025. But future natural gas exports from Uzbekistan shouldn’t be ruled out yet.

Uzbekistan could become a major natural gas exporter with smart reforms and a little geological luck. There are some signs for optimism: Tashkent launched energy sector reforms, set a (potentially unachievable) goal of tripling natural gas production to 150 Bc, by 2030, and invited teams from the U.S. Geological Survey are partnering with the Uzbek Committee for Geology to identify shale oil and shale gas deposits. If Uzbekistan has significant, economically recoverable reserves (and that’s a big if) then the country’s energy trajectory could change quite rapidly.

Finally, Uzbekistan has excellent wind resources and inked a 100-MW wind power project with Saudi developer ACWA Power in December 2021. If wind energy and other renewables can displace domestic natural gas demand, Uzbekistan will become a much more formidable natural gas exporter.

But the giants loom large

Beijing and Moscow surprised many observers when negotiations for the Power of Siberia-2 natural gas pipeline dragged on beyond the February 4th Xi-Putin bilateral meeting. There may be several reasons for the prolonged negotiations: trends in natural gas/renewables markets, the declining attractiveness of megaprojects, Beijing’s desire to maintain a plausible distance from Moscow amid a potential war in Ukraine – and China’s interest in Central Asian natural gas. Beijing will be watching Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan very carefully in the year ahead. If Serdar Berdymukhamedov can govern Turkmenistan effectively, or if Uzbekistan catches some geological breaks, then the region could become a much greater exporter of natural gas.

Glory to Ukraine,

Joe Webster

The China-Russia Report is an independent, nonpartisan newsletter covering political, economic, and security affairs within and between China and Russia. All articles, comments, op-eds, etc represent only the personal opinion of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the position(s) of The China-Russia Report.